|

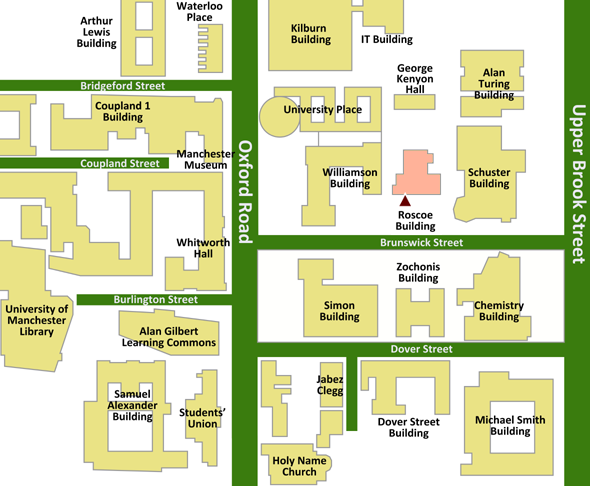

iCHSTM 2013 Programme • Version 5.3.6, 27 July 2013 • ONLINE (includes late changes)

Index | Paper sessions timetable | Lunch and evening timetable | Main site |

|

iCHSTM 2013 Programme • Version 5.3.6, 27 July 2013 • ONLINE (includes late changes)

Index | Paper sessions timetable | Lunch and evening timetable | Main site |

Leonardo has often had an ambiguous treatment from historians. Historians of art have never dealt with anything that looks to them so ‘scientific’ and historians of science have never had to deal with diagrams that are so beguilingly beautiful. The difficulties are partly caused by the narrow specialisms of our day. In Leonardo’s time the pattern of division into recognised areas of specialised intellectual and practical work were very different. The obvious division is largely social: between university education, in Latin, and practical instruction, in the vernacular, but the borders seem to have been fairly porous (at least in Italy). Unlike university graduates, trained in the arts of the trivium and the qualdrivium (the four mathematical ones often called ‘sciences’), craftsmen were expected to make direct use of practical knowledge in their workplaces. In the practical world, ‘art’ also had a specialised meaning for the trades associated with guilds; for instance the wool guild was called the Arte della Lana. These changes in the meaning of the terms ‘art’ and ‘science’ can make it difficult to use “actors’ categories” properly, but whatever terms one uses it is clear that the intellectual map was very different from what it is today and that craftsmen (among them painters and sculptors) regularly brought considerable ‘scientific’ knowledge to their work.

In recent years some bridges have been built across today’s disciplinary divide, and the emergence of a healthier body of literature on Leonardo offers some opportunities to historians of science to integrate him into a viable image of the natural philosophy, mathematics, medicine and technology of his time - and, of course, to assess his possible contributions to what happened next.